The Bill Reid Gallery kicked off a series of talks about artists from its Continuum exhibit with a slide show by Michael Dangeli, a Nisga’a artist who has started to receive recognition in the last few years. The choice was lucky or inspired, because Dangeli is more articulate about his work than most artists, and has clearly thought carefully about what he is doing.

The Continuum show is supposed to be about the conflict between traditional and contemporary influences in Northwest Coast art. And, in fact, Dangeli was introduced in terms of this conflict. However, he immediately made clear that he rejects such a dichotomy in his own work. Calling his work “traditionally contemporary,” Dangeli made clear that he considers his work a continuity of the past, both an attempt to reclaim it and to expand and to adopt it.

One reason why Dangeli is comfortable with the paradox of living with opposites is that he sees the rest of his life in such terms. Nisga’a by birth, he has lived in the United States and Vancouver, far from his nation’s territory. Deeply interested in his cultural past, he is also aware that he is a modern urbanite in his day to day life. Spiritually inclined, he is also a veteran of two tours of duty abroad in the American military. With such tensions, those between the traditional and contemporary must seem like just one more.

Another reason that Dangeli can have the attitudes he does is probably the fact that he is actively involved in the cultural revival of his people – something that seems especially unusual for an urbanite. During his discussion, Dangeli talked of pieces of art being given as payment for services, and at potlatches, as well as important events such as a betrothal. He talked, too, of being groomed to take over a chieftainship, and of his hesitation about taking on an even larger chieftainship recently. He talked about his dancing, and of acquiring songs and dances and inventing new ones, and of exploring the distinctions between male and female powers and responsibility with his finacee.

Unlike many First Nations artists, Dangeli seems either fortunate enough or determined enough to have lived with a sense of tradition from an early age. Consequently, it is easier for him than many artists to see a continuity rather than an opposition.

This continuity seems to affect his art very strongly. He talked of preferring that his gallery pieces not have eyes that would make them danceable, and of his relief when he managed to buy back an early exception to this preference. He talked, too, of making one of the first stone masks for well over a century, and having it danced.

But the strongest evidence of his artistic continuity came at the end of his talked, when he uncovered three pieces of his work that are reserved for ceremonial purposes: The mask he bought back and modified with a pieced of Ainu cloth; the stone mask, and a frontlet worn by his fiancee. He explained that he generally kept them covered, and treated them as living spirits, requesting that people look them over a few at a time so as not to overwhelm them. It was unclear to me whether any power in the objects was innate or resided in the respect shown to them, but his attitude was curiously moving.

Even if you didn’t share his cultural background or beliefs, they were obviously alive for him – either never having died or after being carefully revived, or some combination of the two. Clearly, he had fought hard to make them meaningful to himself and those around him, and I believe that he has largely succeeded. At the very least, he demonstrated to the audience that his cultures were still ongoing and hadn’t stopped developing with the European conquest.

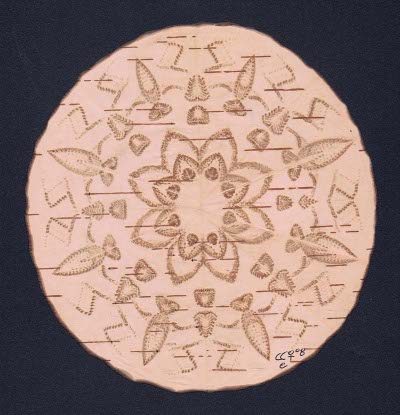

All this says nothing directly about his work, which ranges from the traditional to the modern, with a variety of color palettes and a frequent emphasis on collaborations with other artists – or “brothers,” as he called them.

I have liked what I’ve seen of Dangeli’s work in the past, and, by the time he had finished talking, I had a much clearer sense of why, and an increased interest in what he might do in the future. And, really, what more can you ask of an artist’s talk? With several dozen slides and intelligent commentary, Dangeli sets a high standard for the next speakers in the series to match.