Aboriginal artists in British Columbia have been combining traditions for some years now. Preston Singletary, for example, has collaborated with Maori artist Lewis Gardiner, while Terrance Campbell is strongly influenced by the jewelry of the American Southwest. But I admit I was skeptical about the collaborations of Mike Dangeli and Don McIntyre. Maybe the problem was my own ignorance, but I wondered how much artists like Dangeli in the Northwest style and McIntyre in the Woodlands style could exchange, beyond good will.

However, in practice, the mingling of traditions works much better than I expected in “East Meets West: Throwing Power,” Dangeli and McIntyre’s combined show currently at the art gallery in the Student Union Building at the University of British Columbia.

The main reason, I suspect, is the obvious closeness of the two artists. Dangeli and McIntyre share studio space and are adoptive brothers. They share such a sympathy that at times, they say, they have trouble remembering who painted which line when they collaborate.

The mixture of their style may be sometimes jarring, but it succeeds because, while both Dangeli and McIntyre show a firm understanding of their respective traditions, they are also concerned with adopting those traditions to contemporary urban life, often with a sense of humor that begins with the titles of their works and continues with their choice of subject matter. Despite the large differences in traditions, this similarity of outlook allows them to meet in the middle, as their paintings do literally in the galley.

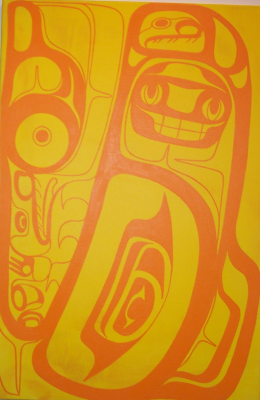

If you look at a selection of Dangeli’s work with any knowledge of the northern formline style, it immediately becomes obvious that he is intimately familiar with the tradition. And some of his work does not stray very far from that tradition, apart from the selection of colors.

However, in many of his pieces in this show, Dangeli’s rendering of that tradition is a departure from the norm. In the classical northern tradition, ovoids and U-shapes are rendered as though from a template – in fact, in large scale projects like house-fronts, artists often work from stencils.

Dangeli does work in this tradition. However, just as often – and perhaps increasingly – he favors a looser, hand-drawn rendering of classical shapes – a sketch as opposed to a smoothly finished work. Often, too, he combines shapes in non-classical ways. The result is that, where in his tradition, formlines tend to flow together, dragging the eye through a work, Dangeli’s looser renderings sometimes seem fragmentary and disjointed.

Perhaps the effect is a stylistic commentary on the survival of the northern tradition in industrial urban life. If so, the style is well-suited to Dangeli’s habit of commenting on this lifestyle.

The titles alone indicate his on-going commentary on the modern relations between First Nations people and this lifestyle, for instance, “Bright Shining Lie,” “For Those Who Had to Hide,” and “We Will Not Be Boxed In. Often, the titles are referenced by the techniques in each work, so that “Surviving the White Wash” literally has a wash of white over everything, while “We’re Not Open for Business,” an anti-Olympic statement,” has the shape of a Closed sign.

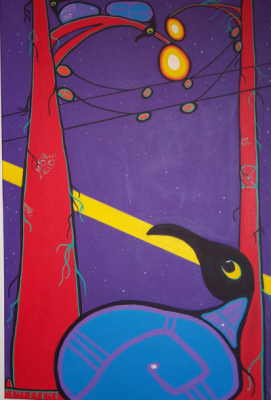

Don McIntyre’s relation to his tradition closely resembles Dangeli’s. Like Dangeli, McIntyre sometimes produces a piece that fits comfortably within his tradition, as in “A Place to Come Back To.”

Yet even when McIntyre appears to be working in the tradition, first impressions can be deceptive. His apparently innocuous drum (shown above), if you look closely, shows the union of sky and earth as an act of sex, and his title for this depiction of creation is “The Big Bang.”

Yet, where many Woodlands artists continue to depict natural scenes that have little in common with the cities in which they live, McIntyre tries to advance his school of painting by transferring its traditions to what he sees around him.

At times, the difference is subtle. As he pointed out to me at the exhibit’s opening, “Natural Urbanity” could easily be a classical work, if the streetlights were replaced by trees. At other times, as in “New Counsel,” nature creeps into the cityscape only in small oases, like the log that the birds in the canvas cling to.

And, as in Dangeli’s work, McIntyre often turns his extension of his tradition into social commentary. In “(Dis) Placed Illusions,” for example, McIntyre combines an inukshuk, the symbol of the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games, with a sleeping polar bear, drawing a line between cultural appropriation and global warming .

Combined with their friendship, such similarities make Dangeli and McIntyre’s collaborations exactly what collaborations should be: not just a juxtaposition, but something that neither could achieve by themselves.

For me, the most successful of the several collaborations on display was “Ben Couver: Olympic Gluttony.” The central figure, with its extended belly, fits in well with McIntyre’s style, in a way that it would not into Dangeli’s.

Yet, at the same time, Dangeli’s image of broken coppers being thrown into the water adds its own dimension. Moreover, the combination of Dangeli’s self-consuming two-headed serpent and McIntyre’s Wendigo provide two complementary images of destruction.

“East Meets West” is a small show, but it is an ambitious one. To its credit, though, it convincingly draws parallels between the two traditions in the show, and produces intriguing art in the process. While the gallery may be obscure for many people, it is well worth searching out just to see this show.