For many modern Northwest Coast artists, improving their skills means discovering their culture. Kaska/Tlingit artist Dean Heron is no different, except that he came to his art and culture later than most of his peers – and, that, in pursuit of both, last year he moved north to Terrace, instead of staying in the south where many NorthWest Coast artists now spend at least part of the year.

“I was adopted as a child,” Dean explains, “and grew up in a non-First Nations family,” mostly in Whitehorse, Kitimat, and Powell River. “I had grandparents who lived in Victoria, so we’d often go down to Victoria in the summer time. My parents always used to drag me to the Royal British Columbian Museum to look into my culture, but at that point I was six or seven, and I was more interested in riding my bike, playing street hockey – being a kid.”

Creating the Watchmen

Then, when Heron grew up, he worked as an assistant manager at a Milestones restaurant, and later in the IT department of the British Columbia Ministry of Health in Victoria.

Heron did have a general interest in art of all sorts, and he remembers a two-week survey of First Nations art when he was in Grade Seven in Kitimat. However, it was only after he met his wife Therese that his interest in his ancestral culture and art began to take shape.

“She was very inquisitive, always asking me questions about Tlingit culture,” Heron recalls. “We’d go down to the Royal BC Museum and she’d ask me all sorts of questions. And I was just blank. I didn’t really have any idea.”

Then, one Christmas in the early 1990s, when they were both students and short of money, Heron was pondering how he could give presents. “I had no idea. So Therese said, ‘Why don’t you create something?’ I think I laughed out loud, actually. I didn’t think I had an artistic bone in my body. But she went out and bought a book on First Nations art, and that was the beginning.”

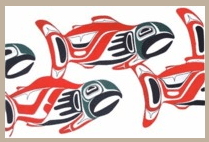

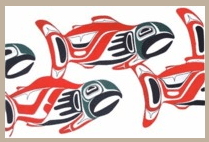

Returning Sockeye

Making the artistic connections

Even then, for years art was more a hobby than anything else. Heron know no artists, but he received encouragement from Victoria gallery directors such as John Black and Elaine Monds. “I would take my early paintings down to Elaine or John Black, and get criticisms on them and come back and produce something else.”

At the time, Monds’ Alcheringa Gallery was displaying the works of master carver Dempsey Bob and his star pupils Stan Bevan and Ken McNeil, although most of them sold quickly. Heron also remembers visiting Vancouver to see the Inuit Gallery.

“But what really did it for me was a book that Dempsey Bob had produced with the Grace Gallery called Dempsey Bob Tahltan Tlingit – Carver of the Wolf Clan. It was this little catalog, way out of print now – I don’t know if you could even find it. There was a picture of a wolf forehead mask, and I had never seen anything like it. It was distinctly Dempsey Bob’s style – it was brilliant. And I just went, ‘Wow! That’s exactly what I want to be doing’ – although at that time I didn’t really know how I was going to do it.”

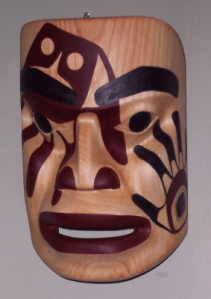

Moon Mask

Then, somehow, “it all just sort of fell into place for me.” A few weeks after his family moved into a house in Victoria, he met Dempsey Bob’s son and his family at a children’s birthday barbecue. A couple of weeks later, he met Bob himself, “and it changed everything.”

Bob invited Heron to Manawa – Pacific Heartbeat, an event sponsored by the Spirit Wrestler Gallery in Vancouver featuring Maori and First Nations artists from British Columbia. There, Heron says, “I realized just how rich the culture was, and just how much I’d been missing.” Near the end of the event, Bob mentioned that the Freda Diesing School was about to open at the Terrace campus of Northwest Community College, and invited him to enroll and learn to carve.

Finding roots in the north

Deciding to accept Bob’s offers “was a giant leap of faith for me,” Heron recalls. His children were six and one, and both Heron and his wife had jobs in the provincial Ministry of Health. “But I never looked back. I think it was the best decision I ever made.”

Killer Whale Comb

After Victoria, life in Terrace “was a huge culture shock. We had everything in Victoria. That’s probably what I miss the most – having a good theater and good restaurants to choose from,” Heron says.

However, the adjustments in daily life soon seemed unimportant compared to what Heron was learning about his ancestral culture and art. Suddenly, Heron was being taught by Dempsey Bob, Stan Bevan, and Ken McNeil – three artists he had admired for years.

Today, Heron praises them for their commitment towards art, their professionalism and work ethic, and their dedication. “Although established artists, they are always learning and pushing themselves forward – and thus pushing the art forward,” Heron says. “As well, they share all their knowledge with their students. Dempsey always says, ‘Why wouldn’t I share it? If I did not, we could lose all that we have gained in a generation – it is why I am here.’”

In the new environment, Heron found his relationship to traditional culture and art changing.

“Back when I was working on art on my own, I didn’t know the rules completely. Working with Stan and Ken and Dempsey, the whole idea is that you learn the rules and make them your own. Then, you can star innovating. But you have to work from a base of tradition, which the school does.

“The first eight weeks of school, all we did was draw ovoids and U forms and secondary figures. And they break down the components of the design, so they do wing design one week and they do head designs another week. Then they’ll do feet designs and tail designs, and then you put the pieces together. The first year, there were only seven [students], so it was a really tight group of friends.

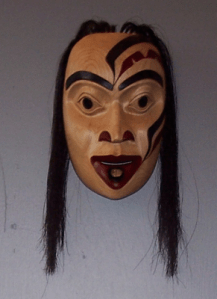

SmallTlingit Portrait Mask

“Another thing that Stan and Dempsey have really convinced me of is [the value of] collecting books. At the time I was working on my own, I was looking at galleries and contemporary works of artists like Robert Davidson, Joe David, and Art Thompson, and I never really gave any validity to the old works that are in museums and collections. That was my mentality – that’s a long time ago, that’s history. But I think everybody’s who’s doing the art and is a professional will look at the old art. [The old artists] are still pertinent today. Their advantage was they lived the art. The art was around them all the time. They used the spoons, they used the bowls, and they saw the regalia all the time.”

The result of this discipline and re-evaluation, according to Heron, is that “I’m starting to realize that there’s a lot more rules involved in creating pieces. You can’t just go out and create a frog headdress without getting permission from chiefs or elders. I’m starting to learn a lot more of those rules, where before I just drew and painted what I wanted without any thought of the culture itself. Now, I’m more careful with what I’m creating.”

This new attitude created a crisis of faith when Heron, perhaps motivated by his new sense of traditional culture, looked for his birth family. Although his biological mother declined to contact him, Heron did learn that he was part Kaska, not completely Tlingit, as he had assumed.

“I remember the day I found out, my first thought was, ‘I can’t practice the art. I’m tied to those Kaska roots.’ But I found digging into my family history that there was more of a Tlingit side. So I paint particularly in the Tlingit style.”

Today and Onwards

Now, Heron thinks he might explore the Kaska side of his heritage. “I’m starting to think that as a person I have the right to know where I’m from,” he says. “So I’m looking more into the Kaska side.” In the summer of 2010, he hopes to take his family to Watson Lake for Kaska Days.

However, whether he will explore Kaska art remains uncertain. “It’s much different from the coastal art. A lot of it is beading, and moose antler carving, drumming and singing. I think they were a more nomadic people [than the Tlingit]. There’s not a lot of information out there.”

Meanwhile, Heron is keeping busy. In the fall of 2009, he completed a mural for the Snowboard Pavilion at Cypress Mountain for the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games. “I’ve had lots of people comment on it, via email and letters,” he says.

Snowboarding Mural, Cypress Mountain

.

In addition, for much of the last year, he has been painting designs for a longhouse on the grounds of the Terrace campus of Northwest Community College. Stan Bevan is doing the formlines, and Heron and student Shawn Aster are doing the secondary elements. Currently, the interior screens are done, and the house front is being completed. The longhouse is scheduled to be completed in early May.

Dean Heron at work in the longhouse

When the longhouse is complete, Heron plans to continue carving his own work. In addition, “I have lots of images that I’d like to get printed.” He would also like to begin doing clothing designs, and learning jewelry-making.

Dedicating himself to art and moving into a community that was strange to him was a huge gamble, but Heron clearly feels that it has paid off for him.

“Growing up, I always felt that I was at the front door, but not right inside – always looking through the window and looking at these sculptures and not understanding the whole of them. I mean, I still don’t. And I think that’s part of the experience of being adopted and being First Nations. I’m at the point now where I’m straddling two different cultures, really. I have a non-first Nations family, so I’m getting an outsider’s point of view, but now I’m living in the community and understanding a lot more of it.”

Read Full Post »