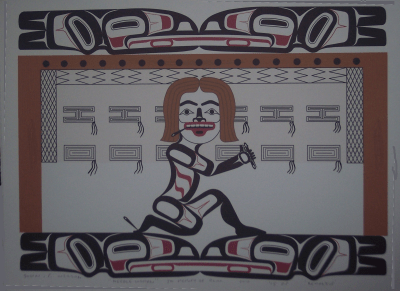

Ten years ago, Wayne Young was a promising journeyman in Northwest Coast art. Taught by such well-known figures as Dempsey Bob and Robert and Norman Tait, he had an enviable reputation for imaginative, often asymmetrical designs, and for fine finishing details on his carving. Now, however, illness keeps him from working. Since new works from him seem unlikely, when I first noticed this miniature argillite transformation mask of a raven and a human on the Alcheringa Gallery web site two years ago, I was immediately interested in buying it.

Not only was I interested in the artist, but I figured that the piece had to be one of a kind. I mean, a mask not only made of argillite, but with two faces? And one no more than fifteen centimeters long and six high? The thick hinges that the outer face swings upon and the fine screws drilled into the argillite are evidence of the difficulty in the construction – and also all the explanation necessary of why no one else is likely to try to imitate the piece.

However, obtaining the piece proved a challenge. When I visited the gallery fifteen months ago, none of the staff knew where it was. In fact, despite the fact it was still on the web site, they could never remember seeing it, and were sure it must be lost. However, three months ago, I queried again. This time, the gallery director answered, and could locate it.

Ordinarily, I don’t haggle over price. However, ten months previous, the mask had been part of an on-site auction, with a quick price that was two-thirds the listed price. Since the gallery had had the piece for seven years, I sensed it might be eager to sell it, so I offered the quick price. It was accepted, and I took a day trip to Victoria primarily to carry it safely home.

I declined the frame and beige and brown matting the gallery had added. I thought the frame did not do the mask justice; I am currently awaiting an argillite stand to display it properly.

Unfortunately, too, time has not been kind to the piece. Another artist who remembers seeing the piece when it was new remembers the outer mask closing evenly. Now, one hinge is slightly twisted, and one side of the mask is lower than the other when closed. A drop of glue on a couple of the screws might be useful, too, and perhaps a replacement of the black cord on the controls.

However, despite these imperfections, I consider the mask well worth having. The carving is simpler than most of Young’s work, but the lines need to be bold on a piece of such minute dimensions if they are to be discernible. Finer lines would be nearly invisible, and therefore wasted – nor would argillite lend itself to them. The fact that Young knew the restrictions of the size and the medium says a lot about his skill as an artist.

I could almost believe that Young deliberately set out to challenge himself by putting obstacles in his own path. If he didn’t, he must have soon discovered them. But, either way, he overcame the obstacles, not with inlays and other distractions, but with a well-designed, cleanly carved, understated bit of excellence. I consider myself lucky to have obtained it, and my only regret is that new pieces from Young are unlikely.