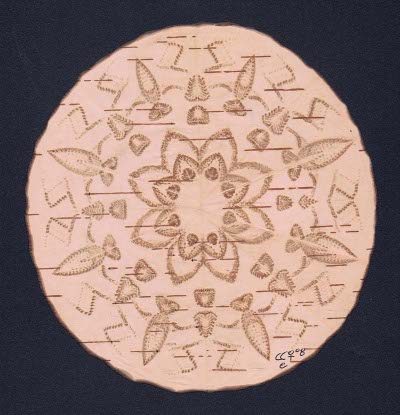

When you first hear of birch bark biting, it seems so unlikely you might assume that someone is having a joke at your expense.

But the truth is, birch bark biting is one of the most intricate and least known of First Nations arts. Concrete knowledge of the art is hard to come by, but, according to Jadeon Rathgeber of Half Moon Studios, whose mother and sister are two of the last practitioners, birch bark biting was widely practiced through North America for centuries, and very likely millennia. Rathgeber and his family are trying to revive the art, both in education and in business.

Birch bark biting is exactly what it sounds like: The making of patterns in bark through careful bites. Traditionally, it is an art done by women, in which the artists fold the bark so that it can fit in their mouths, and visual a pattern as they create it with delicate bites, at times one tooth at a time.

“What I’ve found out about the art is that anywhere they had birch trees, they’ve had birch bark biting,” Rathgeber says. “It could have a ten thousand year old history. Nobody really knows. When Contact happened, it sort of got lost along with all our other ceremonies because it was outlawed.”

What is known is that three century old Chippewa examples are in the Smithsonian in the United States. Rathgeber has heard of a recent dig in Shuswap territory that unearthed samples that may be three thousand years old. The art is definitely known to have been widely practiced in eastern and central North America, and there are even rumors of it being practiced on the northern coast of British Columbia. A student at the Freda Diesing School, for example, reports hearing his teachers list birch bark biting among the lost local arts.

Exactly what samples of the art were used for is equally undocumented. However, Rathgeber suggests that the art may have been used to create hunting and fishing maps, and to pass cultural and ceremonial secrets between generations.

“I call it the first Indian printing press,” Rathgeber says.

Examples of the art may also have been used as the equivalent of wampum belts to commemorate exchanges between different groups. Among the Cree, it was also used in historical times as the pattern of bead work, laid directly over the leather the beads were sown to.

The best-known biter in modern times was Angelique Merasty of the Cree Nation, who lived much of her life in Beaver Lake, Manitoba. Rathgeber’s mother, Pat Bruderer (also known as Half Moon Woman), knew Merasty for over two decades, and sometimes assisted in the sale of her work. When Merasty died about fifteen years ago, Bruderer began teaching herself the craft. Bruderer is now regarded as the foremost birch bark biting artist. Perhaps three or four other biters exist, but none approach her skill.

The making of a piece of birch bark biting begins with the gathering of the raw materials. In Rathgeber’s family, the gathering is usually done by his step-father. The bark is taken by trees of the right size that are free of knots after a tobacco ceremony in which the harvester asks forgiveness for what he is about to take. Large strips are sometimes taken, but never enough to kill the tree.

When Bruderer receives the bark, she sorts out the most suitable pieces, and peels them away until they are only one layer thick. The peeling is a delicate craft in itself, in which one rough motion can destroy a piece of bark. Perhaps that is why, when Rathgeber says, “No one can peel birch bark like my Mom can,” he speaks with such obvious pride.

Bruderer has her own ceremony to put here in the right mood of calm alertness to work. According to Rathgeber, she does not need absolute silence in which to work, but prefers a setting that is quiet where she will not be distracted. She folds the bark up to sixteen times — “like a xylophone,” Rathgeber says – and works using different teeth for different effects, with one tooth for drawing lines, her incisors for shading, and another for large details. She can use only very light pressure, or else the bark will tear.

Even so, she sometimes does as many as five or six pieces before getting one that is up to her standards. Rathgeber reports that his mother has as many as five hundred rejects that he hopes one day to use in collages. Each piece takes a couple of hours to complete, and is usually done in one session, since it would be next to impossible to resume work after quitting.

When a piece is finished, Bruderer flattens her pieces using a secret twelve step technique that is one of the hallmarks of her work. Another mark of her work is the singeing the edges of her work to give it give it a border. Her work is either framed by itself between two pieces of glass, or else incorporated into other work, such as boxes by other artists.

For many years, the family sold Bruderer’s work for two hundred dollars and upwards. However, now, as Bruderer talks of retirement and focusing on preserving her skills by teaching thems to another generation, the family is starting to husband her output more carefully, limiting sales and raising prices considerably.

More importantly, Rathgeber is also searching for a museum or teaching institution to display the best of her work as well as Bruderer’s collection of Merasty’s pieces. He hopes that by making some of this work public, he can encourage academic study of the art – study that might, for example, help to determine how bite patterns differed culturally, or even through the ages.

When I talked with Rathgeber, he had just heard that the Bill Reid Gallery’s gift shop and the Path Gallery at Whistler had agreed to take some pieces of birch bark biting for sale.

Should you see any pieces, you should have no trouble identifying it for what it is. Mysterious and meticulous, birch bark biting is like no other art you have ever seen.