I’m not looking forward to the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. I never watch sports, and I’m concerned about the costs, traffic, and the virtual declaration of martial law during the games. The fact that I once dreamed of being in the Olympics myself only makes me angrier at the travesty that they have become.

Still, I could almost reconcile myself to the games for the sake of all the First Nations art commissioned for them. Some of that art was on display this weekend at the Aboriginal Art Exhibition at Canada Place this weekend, and I thoroughly enjoyed it – even if the lack of organization at the event seems ominous if it is a foretaste of how the games themselves will be run.

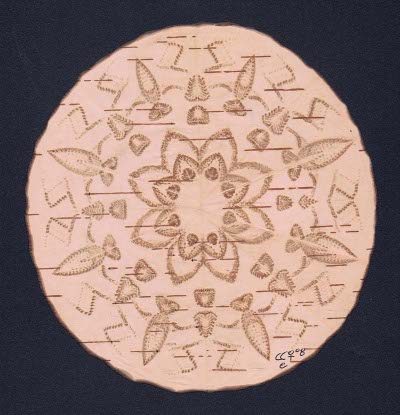

Being appreciative of the commissioned art is something you can file under No-Brainer. I mean, what’s not to like about the art? There’re medals with Corrine Hunt designs, commemorative coins by Jody Broomfield. The snowboarding pavilion at Cypress Bowl will have a wall graced with a new work by Dean Heron. GM Place will have a new work by Alano Edzerza, Nat Bailey Stadium a new work by Aaron Nelson-Moody, and the list goes on and on.

After fumbling badly by making the symbol of the game the inukshuk – a symbol that has nothing to do with British Columbia, much less Vancouver – the games organizers have had the sense to commission locally, focusing on less established artists and on members of the Salish nation, whose territory the Vancouver venues are on. I understand that some 45 works of public art will be added to the Lower Mainland as a result of the games, and I consider that an unalloyed good.

Sadly, though, the Olympic organizers fumbled again in their first efforts to bring most of these works to the public. The display was almost completely unpublicized except for newspaper stories just before the event and some Internet transmission. Even then, it was called an exhibition, so that most people arrived unaware that most of the work on display was for sale – an oversight that bitterly disappointed the artists who had taken tables and paid the exorbitant prices charged for parking at Canada Place.

Even worse, the management of the event was haphazard. I heard artists complain that they were unable to set up for credit or debit cards, and the rumor was that the one bank machine in the exhibit hall required a substantial surcharge to use.

And perhaps the worst thing was that, in order to fill up the hall, the organizers seem to have let anyone exhibit who cared to pay for the table. As a result, many tables displayed tourist junk that did not belong in the same exhibit as the commissioned artists.

For me, the incompetence of the organizing was summed up by the sight of two singers on the stage gamely belting out songs to rows of empty chairs, and a snack bar that had closed down at least two hours before the end of the show. Meanwhile, the exhibitors were strolling around talking to each other.

Such poor planning undermines the celebration of the artists. My impression is that the exhibition organizers couldn’t have cared less if the artists were treated with respect.

Perhaps the organizers can learn, but if this is how they put on such a relatively small event, then we should expect chaos during the games themselves. I might be lured downtown to see the aboriginal market at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, but I, for one, plan to spend the three weeks of the games bunkered down safely in Burnaby, far away from the insanity.