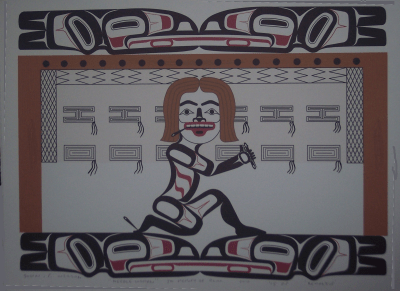

I’ve long admired the graphics work of Dean Heron, but a couple of months ago I realized that I didn’t have any in the townhouse. I quickly remedied that by buying “Northern Raven,” a small acrylic on paper painting that I’m sure will be the first of many purchases.

“Northern Raven” is a split design, with two views of the same figure connected to a central core. Historically, split designs were often used to fill a space, or to wrap the design around a curved surfaced like a handle or the bowl of a spoon. However, they were also frequently used, as here, on a flat surface. They have always struck me as one of the most pleasing forms of symmetrical design, because the fact that one side of the design mirrors the other reduces the static repetition of a perfectly balanced design.

In addition to this natural advantage, “Northern Raven” has several other qualities that make it stand out. To start with, split designs usually have the heads facing outward, leaving a space in the middle. Although reversals of this arrangement are not entirely unknown, they are still rare enough to be noticeable when you see them. By replacing what is usually blank space with design, here Heron creates a far busier design than he would otherwise have, which further helps to break down the staticness of the design.

Another departure from the norm is the use of blue as the secondary color in place of red. This is not an unheard-of innovation in contemporary art, but seeing it in what in other ways is a very traditional piece is somewhat unusual. Added to the pale blue of the paper itself, this choice of colors suggest a cool, icy quality that suggests the first half of the painting’s name (which I otherwise take as referring to the fact that Heron describes himself as a Kaska/Tlingit artist). It also has the advantage of being less arresting than any shade of red, which forces the eye to linger over the design and discover its details at leisure.

However, what really stands out for me is the hand-painted quality of the piece. In some modern First Nations art, the ovoids and u-shapes are geometrically precise, and often drawn by a template, with their curves created by a compass (or, at least, so it appears). If the design is split, the two sides are literally, not just figuratively mirrored, and often created by flipping one side over in a computer drawing application.

By contrast, “Northern Raven”has the appearance of being less geometrically oriented. Much of this sense is created by the thin blue lines outlining the heads. But there is also a suggestion of irregularity in some of the interior elements. Moreover, if you look closely, some of the mirrored elements, like the U and T shapes at the bottom left and right of the design are not completely identical. Such irregularities might easily give a sense of amateurishness, but in this design they add a more human quality, breaking down the symmetry and keeping the design from becoming an exercise in applied geometry.

My only criticism of “Northern Raven” is its scale. With its bold, regular formlines throughout much of the design, the piece deserves to twenty or thirty times its size, and serving as the house front to a longhouse. Otherwise, I consider it a fine place to begin my collection of Heron’s work.