I have two great weakness when buying Northwest Coast art: I love to see artists trying out new media, and I love work that shows the lesser-known figures of mythology. With these preferences, it seems inevitable that I would have bought Morgan Green’s Mouse Woman platter.

Morgan Green is a twenty-five year old artist who seems to be in the middle of deciding what art she wants to do. She is represented in the galleries mostly by her painted leather cuffs, but she has also done fashion design, carved masks and poles, and assisted older artists with painting and metal casting. Add an art teacher and potter for a mother and master carver Henry Green for a father, and it is no wonder that she always seems to be galloping off in all directions (in fact, every time I’ve met or contacted her, she seems about to be preparing for a journey or just returned from one).

The Mouse Woman platter is one of several pieces of ceramics that Green is exhibiting at the Edzerza Gallery. Made from clay that Green recently brought back from Arizona, it is as untraditional as a Northwest Coast piece can be. Ceramics were not a part of the northern coast first nation cultures, and, unlike argillite a century ago or glass in recent decades, have never really caught on, although you can find occasional pieces – usually not very skilled and mostly for the tourist trade.

As for Mouse Woman herself, she remains a bit of a mystery. Few, if any renditions of her survive. But the stories make her a powerful, although minor character. She generally appears as a helper of a hero in a quest. In several tales, for instance, a hero helps a mouse over a log, and then, that evening, comes to a long-house where he is greeted by a noble woman who feasts him and gives him good advice. In other tales, she whispers practical advice about everyday concerns that the hero passes on to his people. In many ways, she is all that Raven is not: domestic where he is a wanderer, a maintainer and restorer of order where he is a bringer of chaos and change, and a representative of civilization where he is the eternal outsider. Where Raven is often a child, she is more often described as a grandmother, perhaps an elder.

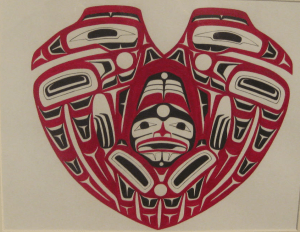

Since no one is quite sure what Mouse Woman is supposed to look like, in depicting her, Green is free to let her imagination run wild. She chooses a simple design that goes well the rough, terra-cotta background – a combination that vaguely suggests petroglyphs, an art form that flourished several centuries before the northern formline became codified. Most of the lines are thin, except for those associated with what Green presumably intends as Mouse Woman’s distinguishing characteristics: her incisors, round eyes and ears. For these features, the lines are heavy, giving them added prominence, and elevating them to the equivalent of the orca’s fin or the eagle’s hooked beak – the features that tell you what creature is intended even if the complete shape is not depicted.

The result is a fragile but alert-looking creature, with ovoids that suggest cheeks stuffed with food. The result is a surprisingly naturalistic figure of a mouse, that, at the same time, also suggests a tiny but alert and active grandmother. How artists of a century and a half ago might have depicted Mouse Woman remains unknown, but I’m sure that they would recognize instantly the subject of Green’s depiction.

I don’t know whether Green will continue working with ceramics. Considering her restlessness, my guess is that she won’t for the time being, although she may return to them eventually. But I suspect that her recent YVR scholarship couldn’t have come at a better time. The Mouse Woman platter is a minor piece (in scope, I mean; at twenty-five centimeters it is definitely not so in size), but it suggests to me an artist who is starting to find the themes that interest her.