As I go through Northwest Coast galleries and web sites, one of the things I am always looking for are miniatures masks – ones under about eight inches in height. We have several wall areas – mostly above doors – that are too small for anything else. Even more importantly, a miniature is a sign of a carvers’ skill. Yet I don’t see many worth buying, perhaps because miniatures tend to be either student pieces or ones designed for the tourist trade, and experienced carvers cannot charge enough for their time to produce many. As a result, I was especially pleased when I noticed that Ron Telek’s “Transformation Mask: Human to Eagle” had come back on to the market. It’s an unusually fine miniature that shows his customary skill and imagination.

How the mask came from Terrace to Vancouver and I picked it up at the South Terminal of the Vancouver airport (which was not, to my disappointment a foggy runway used by single prop planes like something out of Casablanca) doesn’t matter. Enough to say that it did, and I did, and the mask now resides at the busiest crossroads in the hallway of our townhouse.

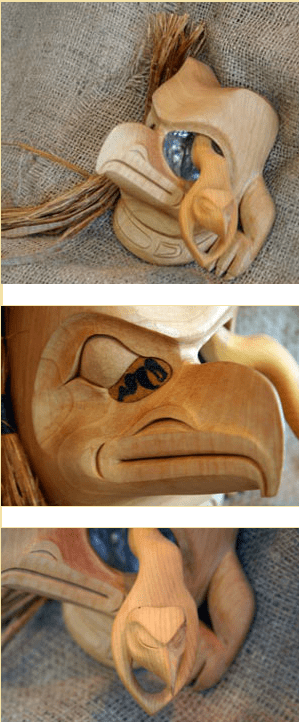

What makes the mask so haunting is its ambiguity. Although a human is turning into an eagle, the dominant face is more of an eagle’s. From the left eye, whose socket is lined with abalone, a human shape with a bird’s head seems to diving. Or so it appears; if you look at how the spirit’s head and arms are arranged, you’ll notice that they suggest another beak. You have to wonder, too, if the shape is the departing human soul or, given the deepness of the eye socket, if the transformation is being achieved by the plucking out of an eye.

Then, if you look at the right eye, you’ll notice that it is bare wood. However, in the eye’s lower third, like a cataract, is a piece of leather with a small shape that resembles the one leaving the left eye. Does that mean that the transformation is all in the eye of the imagination and not literal? That the transformation, or the need for it is based on faulty vision and understanding? Or is it a supreme act of will?

Also, despite the title of the mask, what dominates is a largely bird-like face with a full beak and one taloned foot where its left ear should be. So who is transforming into what? Perhaps the transformation is of the human into the form of his helper spirit or true self. Certainly, the bird face seems serene, perhaps even amused to judge by the line of its mouth on the beak. It is the human spirit that seems in pain or exaltation. By contrast, the eagle seems more stoic and less affected by the transformation. Perhaps for the eagle’s nature, transformation is natural, and it is the human spirit that finds passing from one form to the other uncomfortable.

These ambiguities make for an asymmetrical design – something that is relatively common in Northwest Coast art, but which is part of the foundation of modern mainstream design. By showing elements of both, the mask increases its ambiguity even further. To a certain extent, the asymmetry is reduced by the long cedar braid on the right, but the mask remains, like the figure it represents, halfway between two different states.

In the end, you can say so little about the mask that the uncertainty adds to its fascination. The only thing that you can say for sure about the mask is that it is finished with Telek’s usual attention to detail.

I don’t know why the previous owner decided to sell the mask, but I’m glad he did. Unlike the previous owner, we don’t plan to let it out of our hands. We wonder, though, where we will find other miniatures to match its complexity.