Last night, I was at the reception for Tahltan artist Alano Edzerza’s new exhibit, “Gift of the Raven.” The show features Edzerza’s work of the last six months. Also on display were a number of pieces by Morgan Green, a recent recipient of the YVR Art Foundation Scholarship and (as she may be tired of hearing) the daughter of Tsimshian master carver Henry Green.

The evening started with a performance of “Raven Steals the Light” by Victor Reece’s Big Sky Multi-Media Storytelling Society. The performance was held in the courtyard of the Waterfall Building, the complex in which the Edzerza Gallery is located. It featured a dancer with suitably nervous bird-like movements and a light mask with mirrors for eyes, and ended with him climbing to an overhead walkway to conclude the performance – all in all, a successful blending of the traditional and the contemporary.

Then, the crowd squeezed inside the gallery for the viewing.

The show did not include any new traditional style work by Edzerza. Otherwise, it was a good representation of the different strains in his work. My main problem was dodging the crowd and finding gaps in it that lasted long enough to snap a picture. Combined with the fact that some paintings were hung high, the result is pictures that are less than professional quality (to say the least), but should give some idea of what was on display.

In one corner of the front of the gallery was a collection of Edzerza’s glass boxes:

Elsewhere, you could see some of his experiments with color, such as this collection of closeups of traditional formline designs done in the electric colors of pop-art on a back wall:

The same pop-art sensibility appeared in a couple of contemporary paintings of frogs, which were inspired, I am told, by a tattoo on a woman’s back:

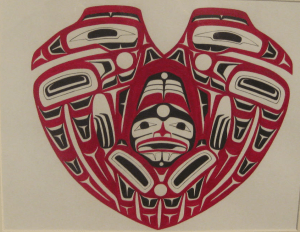

But the major works in the exhibit were the multi-panel ones, like this one that was hung near the ceiling, facing the door:

Another orca design, a triptych, was hung just inside the door, and a triptych featuring ravens on the back wall. The raven triptych was especially dramatic, as one of its panel shows:

All these multi-panel works shared features that are characteristic of Edzerza’s work: A three-dimensional contemporary take on traditional Northwest Coast designs, an experiment with color in mainly grayscale designs, and a dramatic sense of movement that is enhanced by the separate canvases and draws your eyes from one to the next.

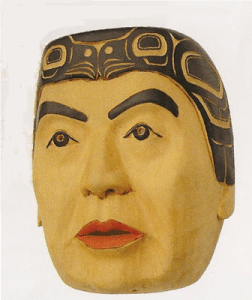

Morgan Green is not as an experienced an artist as Edzerza, but, in the last year, her work has matured quickly. Previously, the work by Green that I knew best were her leather cuffs and a somewhat over-ornate wolf helmet in the gallery, but the works I saw last night shows some other sides to her work, and an interest in different media that, if anything, is even greater than Edzerza’s.

Green’s works included a wall hanging and a variety of earth-colored ceramics inspired by a recent trip to Arizona and the First Nations work she saw there. A plate depicting Mouse Woman was particularly striking:

So far as I know, no historical depictions of Mouse Woman survive. But Green’s rendering seems a reasonable one, with features like the ears, the round eyes and the incisors providing the defining features that you would expect in a traditional design. At the same time, placing the design on grainy ceramic creates a pictograph-like effect, all the more so because the formline is hinted at more than fully realized.

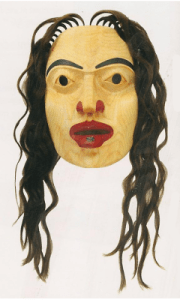

Perhaps the most accomplished work by Green on display was a Dogfish Woman robe she had created for an elder. The design was fairly standard (that is to say, more or less a descendant of Charles Edenshaw’s sketch via Bill Reid), but the cutting of the design and the assembly of the robe made for a first rate piece of work. As Green was discussing it with some of the guests, one of them agreed to model it:

The evening was a fund-raiser, with a quarter of all sales going to the Vancouver Foundation. How successful the evening was a fund-raiser, I didn’t ask. But from the perspective of spotlighting two promising young artists, no one could have asked for more. I came away from the evening with increased respect for both, and an even greater determination to watch and enjoy their future growth.