In January, we missed by hours buying a dragonfly frontlet that Nisga’a master carver Norman Tait and his carving partner Lucinda Turner sold through the Inuit Gallery. The gallery told us that its staff would ask the team to do another frontlet, but we had heard nothing for a couple of months and were just concluding that a second one would not be available when we received email notice that it had arrived.

Did we snap it up quickly? somebody asked me via chat. Put it this way: We received the notice at 3:10. I replied that we would buy it at 3:12 – despite the fact that we prefer not to buy sight unseen, and are saving to pay our taxes. Some opportunities you just have to take when they arise, and, having missed the first frontlet, we were determined not to miss this one.

You see, Norman Tait is one of the four artists we most wanted a carving from (the others were Beau Dick, Stan Bevan, and Tait’s nephew Ron Telek). Tait is one of the most acclaimed Northwest Coast artists alive – and rightfully so, given his attention to detail and his careful finishing. In the last two decades, these distinguishing features have been supplemented by Lucinda Turner, who brings the same qualities to carving.

The only problem is, Tait’s acclaim means that their masks start at about $12,000. While this price is more than deserved, it means that their work is largely out of our price range unless we do some extremely careful financial planning over a year or more. By contrast, the frontlet is more within our price range.

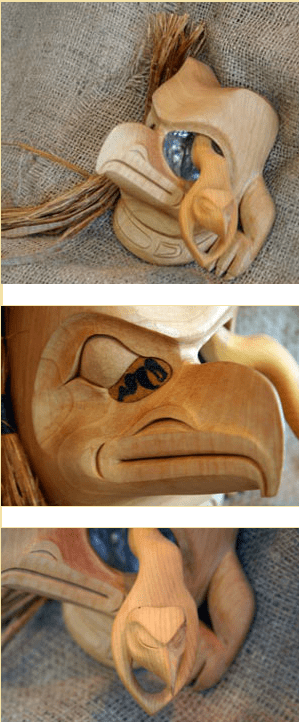

More importantly, the frontlet is a miniature masterpiece in its own right. While in many ways the frontlet’s depiction of a beaver is traditional, it is full of small finishing details — the flare of the nostrils, the roundness of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, the roundness of the tail, the prominence of the front teeth and the curled lip – that lift it out of the mundane.

I like, too, the contrast between the heavy lines and planes of the figure and the lightly inscribed shapes along the border, to say nothing of how the beaver’s ears are incorporated in the border so as not to interrupt the line of the head. All the elements in the border are traditional, yet they are so lightly carved that they almost look like the letters of some unknown alphabet.

In short, everything about the frontlet indicates that it is the work of someone who is as comfortable with carving tools as I am with a keyboard or pen. Although it is undeniably a minor work, it displays Tait’s skill so completely that you can easily extrapolate from it what his poles and larger sculptures are like. As a friend said, having the frontlet in our home is bit like having a cartoon from Picasso.

We hung the frontlet near a similarly-sized piece by Ron Telek. That position gave us the additional pleasure of comparing the work of the master and his former apprentice. We could see that the same attention to detail and finishing was present in both works, but there was nothing you could call imitative in Telek’s work. He had learned the craft from Tait, but each carver has an imagination and style all his own.

Norman Tait and Lucinda Turner: Beaver Frontlet