One of the pleasures of buying art is the thought that you might recognize a young artist before anyone else. The pleasure is not in the fact that the piece increases in value, but in the knowledge that you recognized excellence before anyone else. Currently, buying a print in Northwest Coast art by Robert Davidson or Susan Point requires no special insight – the excellence of both has been well-established for years. By contrast, when Trish and I purchased an acrylic copy of Alano Edzerza’s “The Thief” today, we were taking a gamble.

However, it’s a gamble that we are sure will prove our foresight as Edzerza’s career continues to flourish.

Under thirty, Edzerza is an artist who is beginning to make himself known, especially in glass, graphics, and large scale installations in businesses and offices. Unlike most artists, he also knows the business side of art, and few other artists are in so many galleries, or can boast so many shows so early in their careers.

Last summer, he also became owner of the Edzerza Gallery, which showcases both his work and pieces by other up and coming actions, making him one of the only First Nations artists to run a commercial gallery. I know of several young artists who hope that he will provide a fairer deal than other galleries, and at least one who believes that he does.

I have heard one person denigrate Edzerza for producing giclee prints, as though running off prints from the computer was an abomination rather than a convenience.

More tellingly, I have seen lines in several other people’s artwork pointed out to me that Edzerza might have copied. However, if that is so, the practice is common enough among young artists. Even such an icon as Bill Reid borrowed and imitated at the start of his career, and nothing is wrong with the practice so long as an artist eventually outgrows it.

A more valid criticism is that Edzerza’s imagination is still more two-dimensional than three-dimensional, to judge by his jewelry; not that anything is wrong with his jewelry except that it is not at the same level as his graphics or glass work. Just as importantly, he is also still mastering color, tending to use only one per work.

But, at the same time, Edzerza already shows an exceptional sense of design and a strength of line in his works. Not only are his works effective compositions, but, at least twice, he has found new pieces in closeups of existing works. He simply has an eye for design, and, with this trait, I have few doubts that his limitations will cease to exist in the next few years.

It helps that he seems to have a curiosity and memory for design. The one time I met him, he seemed very current about what other artists were doing, and the way he studied the Henry Green bracelet I was wearing when I passed it to him suggests a capacity to learn.

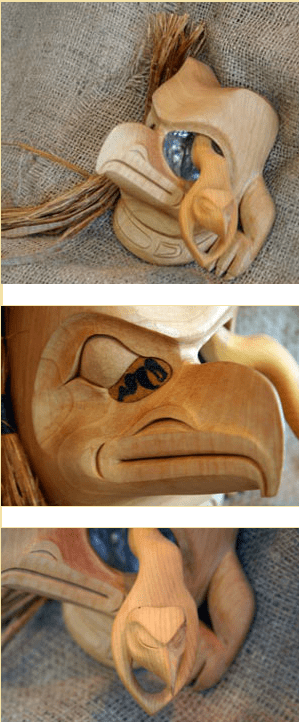

Just as importantly, Edzerza has an eye for drama, tending to show figures in motions rather than static ones. For instance, in depicting the over-used story of how Raven stole the light, in “Smoke Hole,” he focuses on Raven erupting from the smoke hole, charred and on fire. The result is one of the most arresting retellings of that myth that I have ever seen, because he has chosen a dramatic moment to represent.

Although I find graphics like “Smoke Hole” and “Think Like a Raven” powerful, we chose to buy the acrylic of “The Thief” because we believe that it has the potential to be a breakthrough piece for Edzerza. Even if it is not, it is still one of the most effective piece that he has done in a career that already does not lack for highlights.

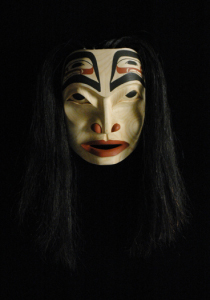

“The Thief” is another depiction of the Raven engaged in stealing the light. However, unusually in Edzerza’s work, it is a still and formal piece. Almost a mask, it shows the child that the Raven has transformed himself into in order to accomplish the theft, surrounded by the body of the bird that he really is. But a hint of Edzerza’s characteristic drama rests in the enigmatic smile of the child, which – unlike the sleepy eyes — is not only decidedly not innocent, but mirrored by the raven’s beak above it. The disturbing smile suggests the theft that is about to happen or is in the process of happening.

Like much of Edzerza’s latest work, “The Thief” is in grayscale. However, there are more shades within “The Thief” than in any other of Edzerza’s works that I have seen. I strongly suspect that “The Thief” is a study in chromatic complexity, and (whether he knows it or not), one of the first steps that may eventually lead to a richer use of color in his future works.

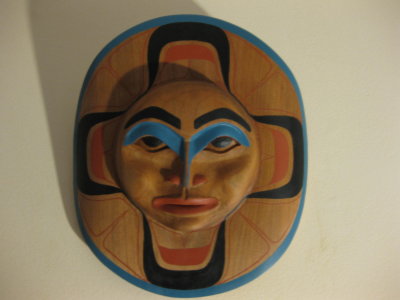

Even if it doesn’t, grayscale is a fascinating world of its own, as anyone who has ever worked in black and white photography can tell you. In “The Thief”’s case, the color palette suggests the moon, which, depending on the version of the myth, is either what Raven steals, or else soon results from his theft. Especially in the acrylic version, the composition has something of the rich sheen of argillite – and, although argillite is generally worked by the Haida, rather than by a Tahltan like Edzerza, the resemblance suggests a carving as much as a graphic. This impression is heightened by the position of the raven’s head over the child’s forehead, an arrangement often seen with transformation figures on masks. Could Edzerza also be using grayscale and the illusion of depth it creates as an exercise to improve his three-dimensional imagination?

Whatever exactly Edzerza was intending, “The Thief” remains the best northwest coast composition I’ve seen this year. It’s a contemporary piece, while remaining firmly rooted in tradition. I am proud to be one of its custodians, and look forward to ferreting out its secrets in the coming years. And if Edzerza becomes as well known as I suspect he might, I will be just as proud to loan it for the inevitable retrospective on his career, when it is recognized as a pivotal moment in his career.

Read Full Post »