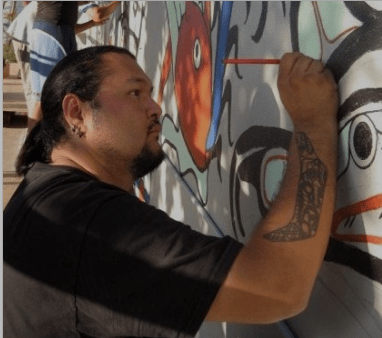

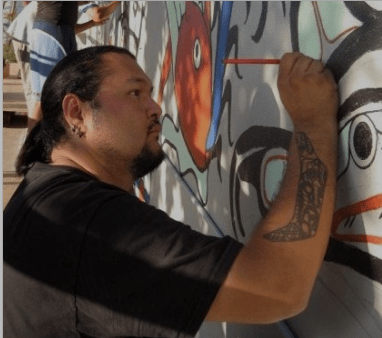

“I’ve been doing art all my life,” Mike Dangeli, the up and coming Northwest Coast artist says. But although he identifies himself mainly as an artist, you cannot talk to him for very long before realizing that he is also many other things — a member of the Git Hayetsk Dancers, the heir to a chieftainship, and a man passionately committed to living in the culture of his Nisga’a, Tlingit, and Tsimshian ancestors within the context of modern technological society. Nor can you separate any of these things from the others, because Dangeli is at least as well known for his artistic work for ceremonies and regalia as for his commercial offerings.

Mike Dangeli

The interconnections go a long way back, although Dangeli took some time to bring them all together. He got his start in art early, making his own dance regalia when he was four or five with his grandmother, artist Louise Barton-Dangeli. He went on to learn acrylics, water colors and oils from her, as well cedar pouches, bags, and beaded necklaces.

At the same time, he learned “everything from weaving to painting to beadwork” from his mother, Arlene Roberts, both individually and as part of the yearly programs at the Chilkoot Cultural Camp in southeast Alaska.

At the camp, he learned from its organizers, Richard and Julie Folta and Tlingit artist Austin Hammond . From an old couple he only remembers as Mr. and Mrs. King, he also learned how to make drums — “that’s everything from taking a deer skin and scraping off the fat to making your own rawhide to string the drum,” Dangeli explains. He enjoyed the process so much that he estimates that by the time he became a professional artist at the age of 27, he had made “over five hundred drums.”

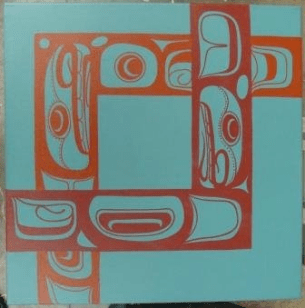

Beaver Drum

Another important early experience was spending the summer travelling on the Alaska ferries with his mother and grandmother, stopping at each port to sell what they made. Dangeli recalls that they did well enough to pay for their fares and his clothes for the coming school year. Through this experience, he also learned from his guardians “how to talk to galleries, to tourist shops, and cultural centers.”

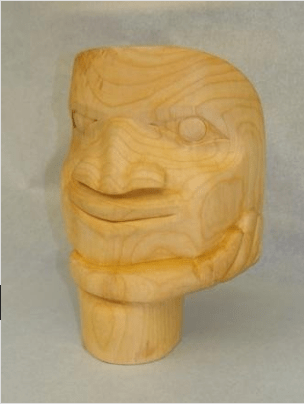

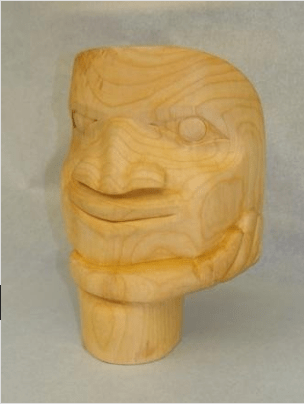

Dangeli’s first training in carving came from his uncle in Prince George. “I spent a summer with him learning basic design and carving bowls and helping him with his work,” Dangeli says. “It was a lot harder than it looked, and I was a teenybopper with a lot of different interests.”

The road to an artist’s life

As a young man, Dangeli staged his own form of rebellion by joining the American army as an Air Ranger. He explains, “I’ve heard all my life that I’m in line to take a chief’s name. When you hear something like that all your life and you have to be good because of it, you decide you’re missing out and think, ‘I’m going to do my own thing.'”

The army seemed a natural choice, because he was thinking of going into law enforcement. “I didn’t see myself as an artist and living that kind of of lifestyle.”

Dangeli spent ten years in the military, rising to Staff Sergeant, but continued carving and designing in his spare time, and visiting family members when possible. It was on these visits that he started gaining a more deliberate understanding of his nation’s Angiosk –traditional territory — and Ayaawx — customs.

Adjusting our frame of reference

When he became a reservist, he attended the University of Alaska and working with his uncle Reggie Dangeli, a historian with the Alaska State Historical Commission. Eventually, he transferred to Washington state.

Matters came to a crisis when he got into a fight with another Staff Sergeant. “He said, ‘That’s the problem with you Indians,’ and of course he said effing Indians, so I smacked him up one side of his head.” At least partly because of the experience, Dangeli decided to leave the military, a move that cost him his university funding.

Finding himself in a well-paying but dead end job, Dangeli drifted towards Robert Boxley’s Seattle dance troupe and eventually apprenticed to him. He went through “a nasty divorce” due to his change of lifestyle, and headed “home to the Nass Valley to lick my wounds.”

The trip got sidetracked in Vancouver when he was asked to finish a pole in Woodland Park.

“I didn’t want to do it,” he says. “It wasn’t a very nice chunk of wood, and I didn’t want to do someone else’s work. So I said, ‘If I do it, it won’t be mine. It will be a community project.'” Hiring ten youths, he finished the pole and celebrated its completion with a potlatch — and, in the process, discovered that he had found himself a community.

“It was such a sad little pole,” he says. “It had been stolen twice, spray painted and a chunk was taken off the side, and someone took a Louisville [baseball bat] to it. It was horrible. But I look at it in retrospect as a physical manifestation of where I was in that moment in time — just beat up and kind of sad. It ended up being something very beautiful — not necessarily the totem pole itself, although it’s still up there and humbling to look at, but because it represents a massive amount of growth. What I created was a community here in Vancouver.”

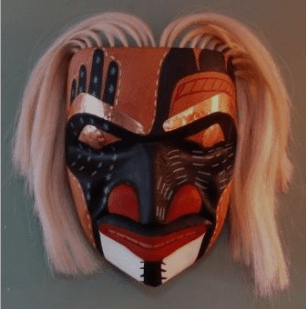

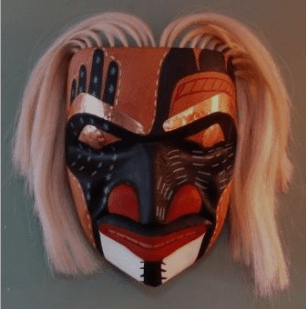

Lifting up my god-son mask

While carving the pole, Dangeli found studio space at the Aboriginal Friendship Centre at Hastings and Commercial. He remains there to his day, running a program called The House of Culture. At first, the program was a cooperative, through which artists passed like Robert Davidson, Reg Davidson, Henry Green, Simon Dick, and Lyle Campbell, as well as younger artists such as Ian Reid and Phil Gray.

More recently, The House of Culture has become a rental space, because “there were a couple of people who had abused the space because they were abusing themselves in their addiction,” as Dangeli explains the situation. Dangeli now shares the space with Woodlands artist Don McIntyre, and Mari Torizane, a Japanese master painter who works as Dangeli’s assistant. Space is also found from time to time for other artists, such as Ian Reid, whom Dangeli regards as a brother.

Such experiences have left him with a strong interest in collaboration. One such result can be seen on the west side of the Friendship Centre, where Dangeli recently painted a mural with Don McIntyre.

Dangeli now works in a variety of media, including stone carving, wood carving, jewelry making, painting, and sculpture. He works twelve to fourteen hours a day and completes 10-30 pieces per month.

“I love a bit of everything,” he says. “You get lost in what you’re working in, so there is no favorite medium. It’s whatever I’m working on. but I always have five of six projects on the go in various stages. You get bored with one and you want to pick up something else. but then the clock’s ticking on a couple of pieces, and you’ve got to get going on them.”

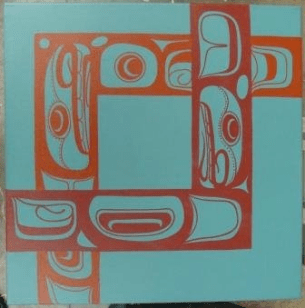

Ceremonial, commissioned, and commercial art

“What’s become really important to me is the performance and ceremonial part of our art,” Dangeli says. “You can ask every Northwest Coast artist, and they’ll tell you that some of the best carvers and west coast artists are the ones who have an understanding of ceremony. It’s a lot different than creating something for the galleries.”

Part of the difference is that a mask intended to be danced “needs the inside to be functional. It needs to be carved to the dimensions of the face of the person who’s wearing the mask.”

Another part is the “responsibility and rights and privileges that you learn by attending ceremonies and understanding them.”

However, the largest difference, Dangeli says, is the spirituality. “In our languages, masks were naxnox— ‘beyond human power.’ These naxnox embodied the wind, they embodied the spirits, and were able to connect us to that spirit world. There’s an understanding that if you don’t treat these naxnox right, they’ll bite you.

“And I’ve seen that happen. I’ve seen a guy who played around too much with a mask and he was dancing on stage at this one event, and he fell right off the stage. It was a good five foot drop. That was part of the mask saying, ‘I didn’t appreciate that.’ I’ve seen it happen in our own dance group. I’ve even had it happen to me.”

Another consideration is the stories that are told in ceremonial and commercial art. “With a lot of our naxnox, there’s an oral history that’s owned by families that I don’t have the right to go and use. There’s even traditions that belong to my family that I would never go and openly sell. When I do art for potlatching or for individuals who ask me for things that display their clan crest, there’s always a different price. I don’t ever charge the full price in these cases, because the best payment is having one of your pieces used. It’s more of an exchange” of services or goods or artwork.

By contrast, “when I’m doing things for a gallery, there are certain stories that are universal to everybody” that can be used instead. Dangeli suggests that this is not a limitation, so much as a situation that calls upon his ingenuity as an artist. He likens the distinction to his experience of dancing, where there are some dances that are not recorded and others that are brought out for public performance.

Dangeli acknowledges that other artists do not observe the same distinctions, but seems to feel that their choices are not his business. “I find it really sad when I see artists breaking those laws [about what can be publicly displayed], but it’s up to their elders, their chiefs and their matriarchs to put them back into line, not us as artists. Although there are some things you look at and think, ‘Gosh, I can’t believe they did that.'”

These distinctions are increasingly easy for Dangeli to observe because, while he has had work in galleries, today, commissions and ceremonial work mean that he does not rely on the commercial art market to make his living. While he praises some galleries like the Eagle Spirit and the Leora Lattimer Gallery, and speaks of their owners with respect, he is concerned that meeting the galleries’ needs can be restrictive for artists.

In fact, in some cases, dealing with galleries can be “abusive,” he says. He recalls selling a drum and a mask to one gallery, and being told by the owner, “‘Now, don’t go drinking this all up in one spot.’ So I looked at him and said, ‘I don’t need this,’ and I ripped up the cheque and handed it back, and took my pieces.”

This experience was reinforced a few years ago by an incident online in which his building and launching of a canoe received condescending criticism from an academic, and others rallied around him.

“It was really wonderful having support from my own people, indigenous people, and people from museums from all over the place, and I let go of that final fear about what people think of my art. It’s none of my business. If you like it, you like it. If you don’t, that’s fine. I think [this attitude] has made me a better artist, and that taking on more commissions has helped me to focus on more personal items and concentrating more on things for potlatches. It’s wonderful to have that freedom, and I would wish it for every artist.”

Art and the community

Dangeli takes his role as an interpreter of his culture seriously. “There is a responsibility, because artists are our historians. They are people who are able to act as a conduit between our culture and our people to the outside world. They’re historians, they’re writers, they’re creators of things that will be used inside those ceremonies. So, yeah, there’s a lot of importance in being a leader and an artist.”

For Dangeli in particular, this responsibility and importance is augmented because he is heir to two chieftainships, one of which he grew up expecting to inherit and one which he has only recently become heir to. This situation, he says, “has affected me in wanting to convey more of my messages. And taking on that larger chieftainship means that I have more responsibilities, both financially and culturally. Financially in the way of making sure that I can get home to attend feasts and potlatches, culturally by being able to create things for my people. It has affected some of what I create and definitely the responsibility not to do anything embarrassing as well.”

Sunset

However, asked if artists help to restore pride to First Nations communities, Dangeli characterizes the idea as an outsider’s view. “I think that, as an outsider looking in, yeah, it could be construed that way. But are you being made aware of it because individual artists are opening your eyes to what’s going on inside those communities? Because, growing up and witnessing all these wonderful things happening within my community, there’s always been pride. There’s always been this sense of beauty and right and wrong and putting your best foot forward. A lot of artists, especially in the generation before mine, have all grown up with that responsibility.

“There’s a huge responsibility being an artists and growing up in that culture, which is why some artists choose not to be part of it. It is too much responsibility. Everyone always wants you to create things for some sort of giveaway or to do this or that. So there has to be a balance.” For instance, Dangeli will often repurpose a piece, or ask permission to make a print of an original painting, so that he can respond to a request without taking too much of his time. He cites Joe David and Beau Dick as two of the older artists who are models of how to find this sort of balance.

“We have a responsibility because we’re able to function in so many worlds, whether it be the white world, within the art world — and it’s not just the art world, it’s the First Nation’s art world as well — within our communities, culturally, and academically and with art historians. I’ve been able to walk in all these worlds, and been intimidated in all of them.

“I remember when Mique’l [his financee] had moved up here. I was looking through some of the readings she had to do for her Master’s in Art History, and I became worried because art historians analyze everything. And I was like, ‘Look, I was poor this month, and people will say, this is Mike Dangeli’s blue period because I didn’t have anything else but blue paint. That was part of my fear: Is what I’m doing now going to be analyzed and picked apart twenty, forty years down the line?. And that was something else I had to let go.”

But, for all the fears, the responsibilities, the obligations and the need for balance, Dangeli clearly remains committed to all that he has taken on. “I love what I do. It’s not a job, and it’s not a career –although it is both — it’s a passion. I absolutely love it. So to be able to have that opportunity to take what’s inside me, to make my thoughts tangible –”

He trails off for a second, then starts in a new direction.

“I’m able only to put out so much in thirty or forty years. That’s a short time in a person’s life. And I started this when I was a little older than most artists. I was 27 when I decided to become a professional artist. so I have a lot of catching up to do. And, at the same time, I’m grateful to be able to create art and to have people see value in it.”

Read Full Post »