Every piece of art, several collectors have told me, comes with a story. Gradually, as I’ve bought art, I realized that this statement is true, so on my spreadsheet for insurance purposes, I’ve created a column where I can type the story of how the piece was acquired.

I have no trouble remembering the first piece of serious art I bought. It was a three inch copper bracelet by Tsimshian artist Henry Green. I’d wanted such a piece for years, and suddenly realized I could afford one. I still remember my breathlessness as I approached the gallery to pick it up, and my sigh of relief when it proved more awe-inspiring than I could ever have hoped.

A couple of months later, I saw that the Bill Reid Gallery was selling canvas banners from a set that had been stored in Bill Reid’s house since 1991. Trish and I bought one, realizing that it was our best chance of affording any work by Bill Reid, then quickly bought another to balance the wall where the first one hung. Soon after, we bought our first mask, a moon by Ron Telek that is both eerie and strangely modernistic.

More soon followed. There was a Beau Dick sketch of a mask, unusual in that, with his carver’s eye, he depicted planes, not lines. The Lyle Wilson pendant Trish won in a raffle at an exhibit – the best $5 that either of us had ever spent. The small Telek mask that I fetched from the South Terminal of the Vancouver airport by walking from the end of the bus line and back again. The Gwaii Edenshaw gold rings we bought for our anniversary. The miniature argillite transformation mask by Wayne Young that I trekked over to Victoria for after Trish’s death and repaired and remounted because it was so magnificently unique. The wall-hanging commissioned by Morgan Green to help her through goldsmith school. And so the stories accumulate, so far as I’m concerned, as innate as the aesthetics of the piece.

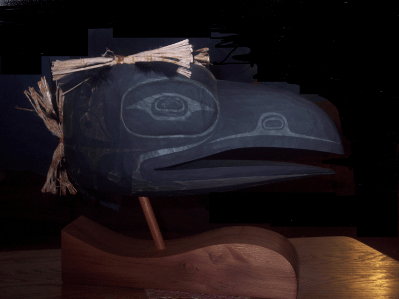

For instance, there’s Mitch Adam’s “Blue Moon Mask,” which I saw in 2010 at the Freda Diesing School’s year end exhibit. It was labeled NFS, bound for the Spirit Wrestler show for the school’s graduates a month later. I happened to mention to Mitch that I would have written a cheque right away had it been for sale – not hinting, just praising – and a few hours later he came back and said the piece was mine if I were still interested. I was, and immediately became the envy of half a dozen other people who also wanted to buy it, but had never had the luck to ask. One of them still talks enviously when we meet.

Then there’s Shawn Aster’s “Raven Turns the Crows Black,” a painting that we had discussed in 2009, but didn’t seem to gel in his mind. After a year, I had stopped expecting him to finish it, and took to calling him a promising artist, because he kept saying that he was still working on it. But he did complete it – making it a Chilkat design (which I had not expected), and showing a promise of a different kind.

Two other pieces were commissions in memory of Trish after her death: John Wilson’s “Needlewoman” and Mike Dangeli’s “Honoring Her Spirit.” I made “Needlewoman” a limited edition of twenty, and gave it to family members for Christmas 2010. Mike’s painting, more personal, I kept for myself, carrying it up Commercial Drive from Hastings Street on a chilly January Sunday, because cabs wouldn’t come to the Aboriginal Friendship Center where I picked it up.

Other pieces were gifts from friends: a print of “January Moon” by Mitch Adams in return for some advice on galleries I gave him; a bentwood box Mitch Adams made and John Wilson carved and painted in memory of Trish; a remarque of Ron Telek’s “Sirens” print, and an artist’s proof by John Wilson and another print by Shawn Aster, both apologies for the late delivery of other pieces.

Of course, such stories mean that I can never sell any of the pieces I buy. The associations have become too much a part of me. But since I never buy to invest, only to appreciate, that is no hardship – my appreciation is only deeper for the personal connections.