A couple of months ago, Haisla artist John Wilson told me about a promising first year student at the Freda Diesing School named Colin Morrison. After seeing some minor pieces by him, I commissioned a painting. It turned out to be his first professional sale.

I am absolutely confident that it won’t be his last – and not just because I would like to boast ten years from now that I had the foresight to see his potential before he became well-known. “The Spirit of the Wolf” is an accomplished piece that illustrates Morrison’s potential better than anything I can say. It is all the more remarkable because it comes from a man in his mid-twenties.

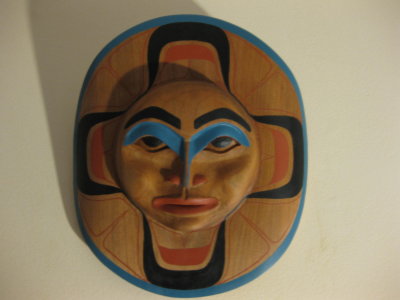

On the surface, “The Spirit of the Wolf” is a traditional piece, reminiscent of Roy Henry Vickers’ work. It shows a strong interest in style, with a variety of ovoids and U-shapes used throughout and a variety of tactics used to control the thickness and joints of the formlines. The sheer number of tactics could easily result in a mishmash, but Morrison controls it by having shapes mirror and contrast each other in disciplined way. The mirroring is especially obvious when the primary and secondary formlines are adjacent to one another.

At the same time, you do not have to look very long before you realize that “The Spirit of the Wolf” has a playfulness that suggests a very contemporary outlook as well. The design is basically a play on the various interpretations of the title, with wolves spread throughout the design – everything from the physical wolf to the Wolf as a clan crest. This dichotomy is suggested by the vaguely yin-yang shape of the overall design.

There is even, Morrison says, several spirits in the metallic paint of the design. So far, I have to admit, I have been unable to detect what kind of spirits they might be, or if anything specific is intended, but I find the idea immensely appealing all the same.

You could even go one step further and say that, since Morrison himself is a member of the Tsimshian Wolf Clan, that the painting itself is a manifestation of a wolf’s spirit.

You might call the painting a kind of Northwest Coast “Where’s Waldo?” If you wanted to say the same thing more seriously, you could say that the content is as inventive as the style.

Asked to say something about himself, Morrison replied, “I’m Tsimshian, Ginadoiks tribe, Wolf Clan. I’ve been an artist since I was young; I started painting when I was 18, and didn’t take it seriously till I was 23 years old. I’ve been painting off and on since that time, trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life.

“Then, one day last year, my Mom started going to a carving class in school. She wanted me to go and dragged me there. I started painting again, and liked what I was doing. My instructor (Harvy Ressel) saw the raw talent and asked me if I wanted to go to the Freda Diesing School. I said yes. Since then, I have found my calling.”

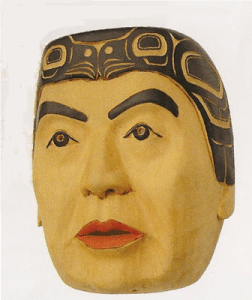

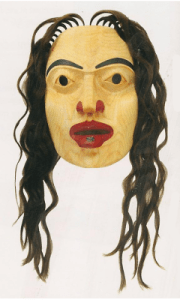

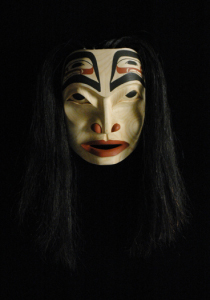

Since doing “The Spirit of the Wolf,” Morrison has completed his first mask and is in the process of finishing his second. I expect that the world of Northwest Coast art will be hearing more from him, but remember (I said, with a certain pride) – you heard of him first from me.