YVR, Vancouver’s airport, is noted for its collection of local First Nations art. I’ve wanted a tour for over a year, but they aren’t always easy to come by, since they involve weaving in and out of security areas. However, today my chance came at last. Together with Ann Cameron, the editor of Coastal Art Beat and my colleague on the YVR Art Foundation board, we followed Rita Beiks, the airport’s art consultant, back and forth through the terminal until I was throughly lost, but marveling at the airport’s collection.

We met at the foot of Don Yeoman’s “Celebrating Flight,” a four-story pole that mixes Haida mythology with Celtic knotwork and a greeting in Chinese. The knotwork and Chineese characters, Rita said, replaced the originally planned figures because of some knots in the wood that made the figures impossible. By itself, the pole is impossible to photograph without a crane and bucket, but when you realize (as I had not) that everything from the panels representing the northern lights at the top to the mosaic on the floor and the moon some distance away are all part of the installation, then taking a complete picture becomes even more impossible.

From the pole, we walked to the terminal’s best-known installation: Bill Reid’s “Jade Canoe,” version of “The Spirit of Haida Gwaii.” The “Jade Canoe” is a copy of the “Black Canoe” at the Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C. However, while the “Black Canoe” is barely visible for security reasons, the “Jade Canoe” is so accessible that people have rubbed the bronze patina off the paddles and some of the other reachable parts of the sculpture. A sign telling people not to climb the sculpture is necessary, and the tradition has grown up that rubbing Mouse Woman’s nose is good luck.

Rita gave a brief history of the negotiations for the piece, which cost three million – an unheard of figure for an airport to spend on art in the early 1990s, and mentioned that the piece was orginally intended to have a copper patina, and changed to bronze only after a phone call from airport official Frank O’Neil to Reid, who at the time was in intensive care. She also pointed out that Lutz Haufschild’s “The Great Wave Wall,” which replaces the nearby windows on the terminal, was chosen as a suitable backdrop to Reid’s iconic piece.

Leaning over the railing, we looked down at the arrival level to Nu-chu-nualth artist Joe David’s “Clayoquot Welcome Figures.” Originally carved for Expo 67, the figures are on permanent loan from the Vancouver museum. Their popularity is so great that they needed a railing to protect them; even so, money is still regularly found in their hands.

We then moved into the secure area for departure and arrivals. Strangely enough, Rita and Brenda Longland, the airport official with us, both had to submit to the usual inspection of their belongings, while Ann and I sailed through without any problems with our visitors’ badges.

We passed display cases with the works of YVRAF scholarship winners from 2010, including Latham Mack’s Nuxalk mask and robe, and Todd Stephen’s drum. Like the other scholarship pieces scattered throughout the terminal, these pieces will be on display until June 2012, when they will be replaced by the work of the 2011 scholarship winners.

The next permanent display was the Pacific Passage in the arrivals area, a combination of diorama and original art.

I had seen the Pacific Passage several times, but always after a long flight that left me rushing to the fresh air, and uninclined to give the art treasures on display more than a passing glance.

That was a mistake on my part, because the display is well worth lingering over. It is dominated by Connie Watt’s thunderbird.

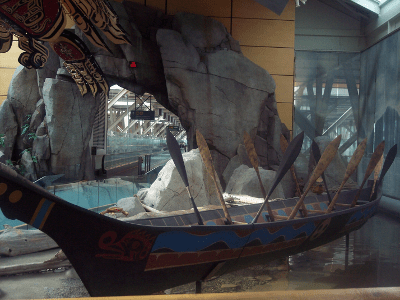

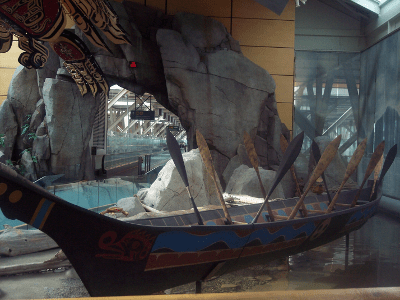

Also in the area is an aluminium panel by Lyle Wilson and a canoe by Tim Paul, as well a number of smaller pieces. Bird sounds start as soon as you enter the area, and I was amused to see the swallows who live in the terminal sheltering in the empty eagle’s nest that was added to the dioramas for realism.

Walking down the overhead walkways, we stopped next at the Musqueam Welcome area, the contribution of the First Nations people on whose territory the airport stands. According to Rita, Frank O’Neill, the airport official responsible for the idea of the First Nations collection, was convinced of the need for the area when the Musqueam chief told him that not having the local nation included there would be like having a sign in Ireland saying, “Welcome to the United Kingdom.”

Accordingly, arrivals are greeted first by the Musqueam, and then by Canada. One of the first sites arrivals see is Susan Point’s giant spindle whorl set against a waterfall – an impressive site even if you have been flying all night (although the palms to each side are incongruous; can’t native plants be used instead?).

Turning to the stairs and escalators that lead down to the custom booths, the first thing arrivals see are free-hanging samples of Musqueam weaving.

Moving to the steps and escalators, below them arrivals see the Musqueam welcome figures. These were originally carved by Shane Point, but when Musqueam women complained about the sagging breasts on the female figure, it was replaced by the less controversial figure by Susan Point that stands there today.

Only as you descend do you appreciate the sheer size of the figures; by the time you are on the same level, you realize that they are enormous.

Our next stop was the artificial river that begins with an installation by Tahltan master carver Dempsey Bob, and winds down to an oceanic aquarium dominated by another piece by Haisla master Lyle Wilson.

Bob’s piece is “Fog Woman and Raven.” It is based on the tale of how Fog Woman, mistreated by her husband Raven, gathers up all the salmon from the streams and smoke houses, and prepares to depart the world with them. A little stiffer than many of Bob’s works, it is still a piece worth lingering over because of the details like the salmon caught in Fog Woman’s hair.

The figures are carved from laminated blocks of cedar – an expensive process that is rarely done because it involves shutting down a mill for the better part of a day. In fact, the first laminted block for Fog Woman was found to be punky inside, and had to be abandoned.

Bob’s tableau is surrounded by chairs, and would be a pleasant piece to linger beside, but, unfortunately no food vendors are nearby, so nobody does. Annoyingly, too, small merchandise displays are crowding the piece (we asked a cashier to move an obscuring sign, but it was back when we passed by again half an hour later)

At the far end of the river, Lyle Wilson’s “Orca Chief and the Kelp Forest” rest on top of an aquarium of fish, so that the chief lies half hidden in the kelp made from glass and looks down at the subjects whom he protects. Rita says that few people look up, and reactions to Wilson’s piece proves her point, since most people looked at the fish moving back and forth, but few ever glanced up to see the art above them.

Our last major stops on the tour were two pieces by Steve Smith. The first, “Freedom to Move,” is a series of painted panels that are intended to slow people down in their hurry through the airport.

Unfortunately, the piece is squeezed into a space too small for it, and the pool that is supposed to surround it is dry, but Smith still managed to slow me down for an appreciative moment or two.

The second of Smith’s installations, “Sea to Sky,” named for the highway to Squamish and Whistler, is a series of drums hung beneath a sky light. What we saw was the second version of the piece, parts of the first having been damage by temperature problems, crumbling with a sound like artillery one winter day (fortunately without anyone being hurt. Smith took advantage of the incident to paint bolder designs, and sold what remained of the first version.

These are only some of the collection we saw today. There were also a number of pieces by Roy Henry Vickers that were originally part of a longhouse that has since been destroyed. The longhouse’s pillars and several other designs are now temporarily scattered throughout the airport, most of them unlabeled.

Display cases throughout the terminal also carried such treasures as Hazel Wilson’s famous “Golden Spruce” blanket, which commemorates the recent felling of a particular tree famous in Haida mythology, Tim Paul’s “ClearCut and Dressed,” and some outstanding non-native work by local artists such as Graham Smith. However, enumerating the entire collection would require a blog five times as long as this one.

For lack of time, we also didn’t get to the “Supernatural World” installation by Dempsey Bob, Robert Davidson, and Richard Hunt on the domestic arrivals level. And the only reason Susan Point’s “Cedar Connection” was included in the tour was that we passed it on the way to the Skytrain and the parking lot as we left.

Still, I didn’t feel cheated by any omissions. After four and a half hours, my brain was as numb as my kneecaps. I had taken in as much art as I could appreciate for the day, and rode the Skytrain home, full of the dazed content that comes from prolonged exposure to fine art.

Read Full Post »