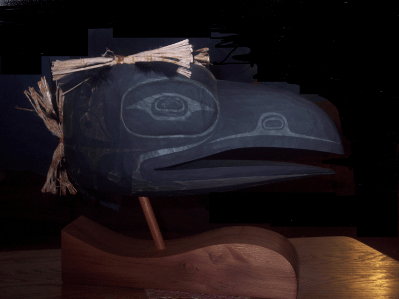

Shawn Patrick Aster’s “Raven Turns the Crows Black” has a longer history than most of the art in my townhouse. Aster took over two years to deliver it, but I consider it well worth the wait.

Aster’s work was brought to my attention by another artist in late 2008, as someone whose work was admired even by master carver Dempsey Bob. I immediately commissioned a piece from him, wanting an early piece from an already skilled artist who seemed sure to make a name for himself.

A few months later in April 2009, when I attended my first year end exhibition for the Freda Diesing School, I was amused to see that others gave Aster’s work no special attention – until he won two awards. Moments later, all his work in the show had sold.

But the commission had progressed little. Aster seemed nervous (I believe it was his first commission outside his family and friends) and couldn’t satisfy himself with the design. A month later, I bought “Raven Heart” from him, but I was still waiting for the commission.

By the next year end exhibition, Aster was looking distinctly apologetic when he saw me. Jokingly, I started referring to him as “the most promising artist” I knew, since he had promised the piece for over sixteen months – although I made clear that I was more than willing to wait. Secretly, though, I had decided he was unlikely ever to deliver. I was disappointed, although I bought other pieces from him.

Then, last March, Aster told me on Facebook that he had finally completed the design. It had apparently changed since he first started designing it, but I was happy to see it. I paid indirectly at the 2011 year end exhibition, and it was delivered by Aster’s fellow Freda Diesing graduate Todd Stephens at the YVR Art Foundation’s reception in May – a good deal of which I spent showing the piece to others and worrying that food might be spilled on it.

“Raven Turns the Crows Black” depicts an episode from the Haida epic “Raven Traveling,” a work that many now consider the common heritage property of all First Nations people on the northwest coast. In the story, Raven the Trickster sees crows roasting a salmon on the beach. They agree to share the food, and Raven falls asleep while he waits for it to cook.

Unwilling to share, the crows devour the salmon. Belatedly worried at what Raven’s reaction is going to be, they put crumbs of the salmon meat on his clothes and between his teeth. When he wakes, they try to convince him that he ate before he slept, but Raven in his anger throw them into the fire, from which the survivors emerge forever singed and black.

Aster’s rendering of the story makes for a unusual design in what is already a tradition apart. Shared by several northwest coast nations but possibly Tsimshian in origin, the Chilkat style is based on weaving patterns. The style is constrained by the limits of weaving, so it tends to consist of discrete blocks of design, rather than the flowing formline found in painting and carving. This tendency makes it both geometric and highly abstract.

Aster’s design shows Raven in the center, his teeth bared (and if you ask why Raven has teeth, I can only reply, why does the parrot in Aladdin? Although, probably, Raven was in human form in the story, shape-changing being his most common power). I interpret the design as showing Raven in two states: in the middle, hungry and asleep, with his wings folded, and at the top center, angry and awake with his wings outstretched.

On the left are the white crows, on the right the black; like the raven, their wings and other features are abstracted into blocks of forms. The designs on each side are not quite symmetrical, with only the outlines of the heads to suggest the transformation in the story.

The background includes the characteristic Chilkat blue and yellow. However, to suggest the fire – and, perhaps, the salmon meat and Raven’s anger – Aster adds red to his design. Although I am far from an expert in Chilkat design, I have never seen any other Chilkat design use red. However, Aster’s innovation succeeds, largely because the red is relatively dark and sparingly used.

The result is one of the most bold-looking pieces of art in my collection. And while I admit that I grew impatient while waiting, I’d gladly wait another twenty-eight months for another work that is equally striking.