Last year, I started the Northwest Coast Art Meetup Group. But the assistant organizer proved unreliable, and, I couldn’t afford renting meeting space in downtown Vancouver every month – a necessity, since I’m in the suburbs. Lacking support, I stepped down as organizer. But I regretted the failure, and was as pleased as I could possibly be when Stacey Jessiman. took over and announced a new meeting.

Last night, a half dozen of us met at Stacey’s house on the west side of Vancouver to hear Bill McClennan, a curator at the Museum of Anthropology, deliver a slide show on the recently-concluded Charles and Isabella Edenshaw exhibit. Meeting in her house helped to keep the atmosphere informal, and the expenses down.

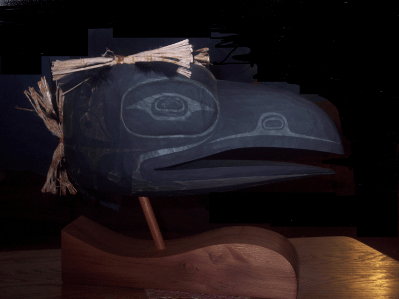

Charles Edenshaw is generally considered the premier Nineteenthh Century Haida artist, and recently his wife Isabella has received the credit she deserves for spruce root weaving of baskets and hats, many of which were painted by her husband. The show at the Museum was an unprecedented bringing together of his silver work (although not, unfortunately, his argillite carving) and her surprisingly well-preserved weaving, and I had visited it twice in the last year.

Not that I objected to seeing slides of some of the pieces, many of which came from private collections or distant museums, and aren’t easy to see. Charles Edenshaw’s work, with its use of negative space, remains surprisingly modern, especially in its use of blank space – perhaps because he heavily influenced artists like Bill Reid and Robert Davidson. Similarly, I am intrigued by the thought that Isabella’s work has distinct knots and patterns that, to an expert, identifies it as hers.

In addition, Bill did a good job of putting the Edenshaws in context, showing surviving pictures of the houses where they lived, and even the general store on the banks of the Skeena where Charles Edenshaw sold his art while Isabella Edenshaw labored in the salmon canneries down the beach.

However, I was equally intrigued by Bill ‘s behind-the-scenes account of the exhibit. The Edenshaws’ descendants number in the hundreds, and perhaps a quarter attended a private viewing and celebration the night before the official opening.

For example, Bill relates that as the descendants entered the exhibit’s gallery, he was surprised to see that many left quickly. Apparently, some were concerned that the spirits connected to the pieces were upset by the chaos of the crowd, and only re-entered after elders performed a ceremony to calm the atmosphere.

Bill also explained that, at any exhibit, some pieces always receive more attention than others, and that he was curious to see what those pieces would be at this one. To his surprise, the main attraction was a blown-up photograph of Isabella Edenshaw. Although the Haida were forced to become patrilineal by English and Canadian society, matrilineal remnants are still strong among the Haida (so much so that some thought the patrilineal descendants shouldn’t be invited), so Isabella was of of more interest than Charles. Many, too, were interested in the Edenshaw’s four daughters for the same reason, and some had never seen pictures of their female ancestors.

In fact, interest was so strong that the pictures were carried out of the gallery into the main hall for the celebration. In the slides Bill showed, the pictures stand in the background, almost, as he said, as though Isabella and her daughters were waiting to speak or to enter the dance floor. For me, hearing about these personal touches helped me to recognize that the exhibit was not just an artistic event, but a cultural and familial one as well.

This information was delivered informally, with Bill propped against a cushion on the floor next to the projector, and the rest of us arranged on the furniture around the fire. It was an atmosphere that rented space could never have matched, even without the buffet of salad, bread, cheese, and drinks that Stacey prepared.

All in all, I’d call it a successful re-launch. I look forward to the next meetings (although I suggest they be potluck, so that everyone can enjoy them). Obviously, the meetup is now in much more capable hands than before.