I have read about and seen something of the culture of the Haida, Tsimshian, Nisga’a and other First Nations of the northern British Columbia coast. However, I know little about the Nuxalk of the central coast beyond the fact that the nation prefers not to be referred to as the Bella Coola, as they once were. For that reason, when Latham Mack, one of this years’ graduates of the Freda Diesing School danced a Nuxalk mask, I was an attentive member of the audience.

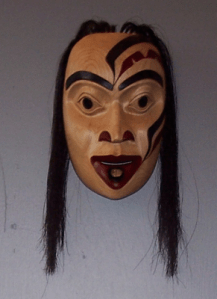

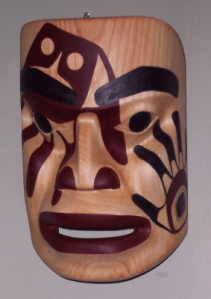

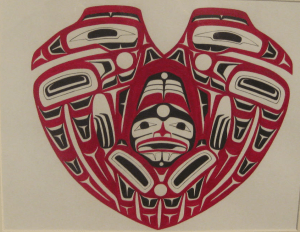

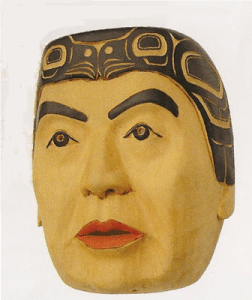

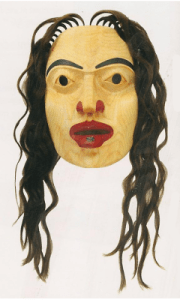

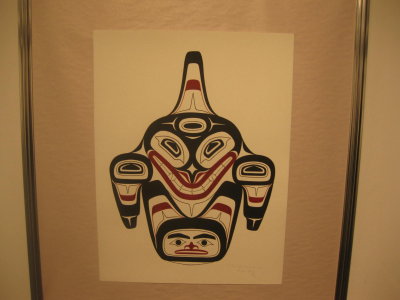

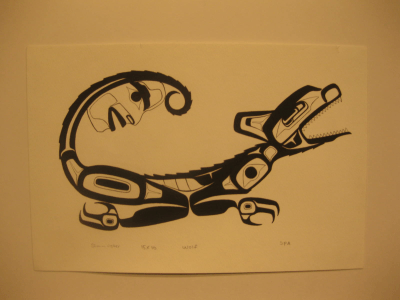

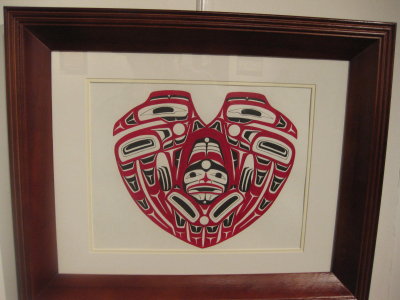

I am used to thinking of Latham Mack, who twice won the YVR Art Foundation scholarship, as a designer more than a carver. Certainly, he has done far more designs than masks to this point, including a limited edition print. However, as part of his final work in the Freda Diesing program, Mack finished two Thunder masks, a blue one for the year end exhibit and the upcoming show at the Spirit Wrestler gallery, and a black one that he has announced that he will keep in his private collection.

Both masks reflect the story of the four brothers who saw a dancing figure on the mountain who created the thunder – an important story in the Nuxalk tradition. The hooked nose and flaring nostrils are a traditional part of the figure’s depiction.The small branches attached to the head, presumably to suggest lightning, are also traditional, although Mack’s mask makes greater use of them than several others that I’ve seen pictures of. This tradition, as Mack emphasized to me, is separate from the Thunderbird of the Kwakwaka’wakw or other First Nations, with the central figure representing the spirit of the storm.

Latham Mack tells me, “Two major dance rituals make up our winter dance ceremonies, the Sisaok (ancestral family dances) and the Kusiut (secret society ceremonies). The Thunder dance is performed by members of the Kusiut society. According to Bella Coola belief, the supernatural ones in the upper land resemble human beings in performing Kusiut dances. Corresponding to the prowess of his patron, the dance of his human protégé is one of the most important Kusiut rituals. Only the strongest of course danced the Thunder because of the movements and physical fitness you had to be in to actually dance it. Only the families who owned the story actually danced it, but as the years have gone by, we have lost the identity of those owners. So now it’s basically owned by the whole Nuxalk people.”

Mack goes on to say that, “The dance of Thunder can be performed with four, two or one masked dancers, depending on the prerogative of the protégé. When the dance is done with four Thunders, these represent the four brothers in the oral tradition. Numerous dances lead up to the Thunder dance, the Herald introduces the dance of Thunder. He beats his stick on the floor and announces the impending Thunder dance.”

Many dances can lead up to the Thunder dance, but, in this case, the performance was divided into three sections, each introduced and narrated by a member of Mack’s family who also provided a rattle accompaniment.

Since the mask had never been used before, the ceremony began with a blessing of the mask by sprinkling down over it.

Then, before Mack’s actual dance, three female members of his family prepared the area in which he would dance with their own dance. It was a stately dance, done with upraised palms and constant circular steps. The narrator explained that this preparation was a traditional role for women in Nuxalk dances.

Then, before Mack’s actual dance, three female members of his family prepared the area in which he would dance with their own dance. It was a stately dance, done with upraised palms and constant circular steps. The narrator explained that this preparation was a traditional role for women in Nuxalk dances.

Then Mack danced. He wore an apron threaded with loose pieces of wood that he shook for percussion, and wooden clappers on his back.

Frequently, he threw himself down on his knees and climbed to his feet again.

His hands and lower arms made constant flickering gestures, as if to shoo people away, but actually to bestow blessings upon the audience.

It was an energetic dance, enough to scare several young children at the front of the audience, who quickly moved away. He also wore cuffs around his ankles and wrists and the modern innovation of knee pads (which was wise, since he was dancing on a concrete floor, and would have otherwise damaged his knees). It was an obviously exhausting performance, powerful and contrasting sharply with the graceful motions of the women’s dance a few moments before

All too often, those of us who are not directly involved in First Nations culture can forget that the masks that we admire have a ceremonial purpose — or are supposed to have. Mack’s dance was a small reminder of this basic fact, and left me wondering where I could find more about Nuxalk culture.

(Note: Ordinarily, this dance is not photographed, but Latham Mack’s grandfather, Lawrence Mack (Lhulhulhnimut), a chief of the Grizzly clan from the ancestral village of Nusq’lst gave permission for those in attendance to photograph it. He also graciously gave me permission to post the pictures I took on this blog. Needless to say, any mistaken cultural references here are due to my ignorance or to lapses in my memory, and not to his kindness. Should anyone see any mistakes, please let me know so that I can correct them.).